Student

Writing

Hum 210 & Engl 390

author-title

table of contents

Short cuts:

![]() Dialogues

Dialogues

![]() Shannon Adkisson: "Chinese

Poetry Translation Issues"

Shannon Adkisson: "Chinese

Poetry Translation Issues"

![]() Christine Clark:

"To Live" [Film]

Christine Clark:

"To Live" [Film]

![]() Meagan

Gates: "The Black Water River" [Red

Sorghum, the novel]

Meagan

Gates: "The Black Water River" [Red

Sorghum, the novel]

![]() Mayumi Kanai: "Chinese

Translation Issues"

Mayumi Kanai: "Chinese

Translation Issues"

![]() Izumi Ota: "Chinese

Translation Issues"

Izumi Ota: "Chinese

Translation Issues"

![]() Marie Kay Patteeuw: "Confucius

and Women"

Marie Kay Patteeuw: "Confucius

and Women"

![]() Mary Uhland:

[Film vs. Novel: Mahabharata & Dream of the Red Chamber]

Mary Uhland:

[Film vs. Novel: Mahabharata & Dream of the Red Chamber]

![]() Unsigned: "The Gambling Match"

[Mahabharata]

Unsigned: "The Gambling Match"

[Mahabharata]

Haiku![]()

![]() Meagan

Gates1 [sound of solitude]

Meagan

Gates1 [sound of solitude]

![]() Cathy Hosford: "Haiku

for You"

Cathy Hosford: "Haiku

for You"

![]() Mayumi Kanai: "Haiku"

Mayumi Kanai: "Haiku"

![]() Nobuhisa Kondo: "Haiku"

Nobuhisa Kondo: "Haiku"

![]() Shannon McKenzie: "Haiku "

Shannon McKenzie: "Haiku "

![]() Izumi Ota: "Haiku"

Izumi Ota: "Haiku"

![]() Keiji Oto: "Haiku"

Keiji Oto: "Haiku"

![]() Unsigned: "Haiku"

Unsigned: "Haiku"

![]() Unsigned: "Haiku"

Unsigned: "Haiku"

Discussion

Papers

Discussion

Papers

![]() Chad Brown: "Drinking With Li Po"

Chad Brown: "Drinking With Li Po"

![]() Mayumi Kanai: "Chinese Translation Issues"

Mayumi Kanai: "Chinese Translation Issues"

![]() Nobuhisa Kondo: "Relationship Between Zen Buddhism and Art

in Japan"

Nobuhisa Kondo: "Relationship Between Zen Buddhism and Art

in Japan"

![]() Keiji Oto: "Asian Poetry in Translation"

Keiji Oto: "Asian Poetry in Translation"

![]() Shawna

Moore: "Mo Yan

Paints Red Sorghum

Shawna

Moore: "Mo Yan

Paints Red Sorghum

Critical

Reviews, Winter 2001:

http://www.cocc.edu/cagatucci/classes/hum210/studwrtg2.htm

Dialogue #3

Humanities 210 (Spring 1998)

CHINESE POETRY TRANSLATION ISSUES

Translating Asian poetry can be an intimidating and challenging experience, especially when one strives to recapture or retain the original sensations and vivid imagery first created by the author. For example, for a Western translator to effectively and convincingly translate Chinese poetry into English; he or she must not only be very knowledgeable and proficient in the Chinese language from which they are translating but also with the English language they are translating to. An in-depth exploration into Chinese culture is also essential. A good translator of Chinese poetry would educate his or herself in regards to China’s history, its geography, political system, familial system, religions, and any other aspect of Chinese culture that might change the context of the author’s intended meaning in his or her poetry.

A good translator researches and discovers the finer details of description and historical facts of each given time period to fully be able to translate each poem as authentically as possible. He or she should illuminate the literary taste of the time period and understand the style and expression of poetry being written during the time period it was created.

One challenge that a translator must acknowledge is the fact that a change in punctuation can alter the whole meaning of a sentence or verse. Another difficulty faced by translators is that many times there is no equivalent word to use to convey the same concept being expressed. The Chinese language does not use connecting words, so a translator adds connecting words within the poetry they are translating to make it more readable, understandable, and palatable to our Western ears, and minds.

A translator must continually interpret, evaluate, and choose the right tone, words, and such to remain as faithful to the original author’s intent as possible.

SONG #76 COMPARISON

Liu Wu-Chi’s translation of Song #76 appealed to me more

than Arthur Waley’s translation of Song #76. I found Liu

Wu-Chi’s translation of Song #76 to be more singular in its

expression and more lyrical and rhythmic. The use of the word

"my" throughout the poem made the poem seem to be more

singular, more personally affected, and self directed in

comparison to Arthur Waley’s translation of Song #76 which

used the words "our" and "we have" in the

same places. Arthur Waley’s translation seemed more familial

based to me. He translates the same line of Wu-Chi’s,

"Do not leap into my homestead;" as "Do not climb

into our homestead." This same line explains why I feel

Wu-Chi’s translation is more lyrical. The use of the word

"leap" instead of the word "climb" invokes in

me a more magical, lighthearted imagery of the poem. To me the

word " climb" depicts a more arduous and laborious

entry into the homestead. Waley’s translation that involved

a more familial basis seemed more traditional to me, yet

Wu-Chi’s use of the phrase "elder brothers" also

seemed more traditional to me.

© Shannon Adkinsson, 1998

Dialogue #6

Engl 390 (Spring 1998)

To Live

In the movie To Live, Zhang Yimou’s biases against China’s earlier politics are strongly felt. In contract to many other Chinese filmmakers, Zhang decided to "leave behind political abstraction and symbolism and depict the works of politics and ideology on a more human level" (Fifth Generation, 172). Zhang wanted to show the effects of politic changes on a Chinese family touched by fate. However, Zhang might also have tried to exorcise some of his own ghosts in the movie as he was caught in the middle of the Cultural Revolution in 1968 as a young man. Instead of being able to attend the cinema academy in Beijing, he was forced to "suspend his studies and, like many of his contemporaries, go to work in the countryside" (Fifth Generation, 174).

In "To Live", he follows the Wu family: Fugui, the father; Jiazhen, his wife; Fengxia, their daughter; and later on, Youquing, their son; through forty tumultuous years in China’s history.

When the movie starts, in the 1940s, Fugui has lost everything including the family house to Long-er, a ruthless gambler. Fugui is devastated but soon understands that losing the house actually saved his life once the communists took over. Later on, while touring China with his troupe of puppeteers, he is enlisted by force in Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist army. The war between the nationalists and Mao Zedong’s communist forces for the control of China lasted from 1946 to 1948. Zhang admirable portrays the triviality of war. Fugui and his friends don’t even know who they are fighting against and pray to live long enough to see their families again. The strongest image is the killing filed where thousands of soldiers have been killed and executed.

In 1949, the communists win the war and Chairman Mao Zedong establishes the People’s Republic of China while Chang Kai shek flees with his troops to Taiwan. Yimou paints the new China as bathed in red, the color of communism. His criticism of the new regime is still strongly felt. He portrays the propaganda surrounding Mao and putting him on a pedestal as the savior of the Chinese people as extreme, even ridiculous and laughable. This is particularly felt during Fengxia’s wedding to Wang. After painting portraits of Mao on nearly every wall in Fugui’s modest house, Fengxia and Wang are married wearing the communist military attire. Later on, they sing an hymn to communism and have their picture taken under a painting of Mao holding little red books standing behind a cardboard ship sailing to overtake the world. However, what I felt was Yimou’s strongest criticism of Mao and his Cultural Revolution in 1966 was Fengxia’s death after giving birth to her son. The Cultural Revolution called for students to "rebel against authority and form units of Red Guards. School shut down, offices closed, transportation was disrupted, and the extent of the chaos, blood, and destruction is still far from known" (Timelines of China 5 132). The Red Guards had raided the hospital where Fengxia was admitted. All of the doctors (who represented authority) were persecuted and sent to camps. The nurses attending Fengxia were young and inexperienced, and could not stop her from hemorrhaging to death.

Yimou’s film was a strong statement against communism. The essence of communism is to protect the people against an elite and provide food and shelter for them. However, in "To Live", the people suffered from Mao’s communism. Children died and families were disrupted when the goal was to make their lives better.

[References are to the 1998 Hum 210 and Engl

390 course packets.]

© Christine Clark, 1998

Meagan Gates

Dialogue #4 - Red Sorghum

Hum 210, Dr. Agatucci

7 March 2001 (Spring 2001)

The Black Water River

In the beautifully described, yet horribly violent Red Sorghum, Mo Yan chronicles the history of a fictional family’s and country’s efforts to survive the 1930’s Japanese invasion of China. Yan takes the beautiful scenery of the Northeast Gaomi Township in the northern Shandong district and contrasts it with the disgusting and graphic violence that wracks this war torn country. He specifically uses the Black Water River setting as a focus. As such a focus, the river was compared to the people living around it – "the heavy Black Water River… was like the great but clumsy Chinese race" (RS 2.3.97). Yan highlights how the river participates in the violent scenes because it is the symbolic representation of what the people are feeling and becoming.

I chose a few examples of this connective imagery from the first two "books" that I thought exemplified Yan’s technique. In 1925 one of the main characters, Yu Zhan'ao, seeks to revenge the kidnapping of his lover (Nine) on Spotted Neck’s bandit gang. In his angry search to find the bandits, Yu had to pass over the "roaring" and "churning" Black Water River (RS 2.10.159). Close to the river crossing, he tricks the bandits to believe he cannot swim or shoot, and then efficiently murders them in cold blood. The text describes it thus:

Granddad (Yu) picked up his pistols as the bandits swam toward the riverbank like a flock of ducks. He fired seven shots in perfect cadence. The brains and blood of the seven bandits were splattered across the cruel, heartless waters of the Black Water River (RS 2.10.163)

I think Mo Yan tries to tell the reader what emotions Yu Zhan'ao experienced around this murder through the river, though he does not specifically say "Yu was angry." The author takes Granddad’s surroundings and transfers his emotions to them, making the "cruel, heartless" river a sympathetic participant.

About fourteen years later, Yu Zhan’ao, his son, and his guerilla gang prepare for an ambush on the invading Japanese soldiers. As they marched along the Black Water River to get to the Jiao-Ping Highway, the river companionably "sang in the spreading mist, now loud, now soft, now far, now near" (RS 1.1.5). Yet after the "famous" battle, the water "sobbed as it flowed down the riverbed" (RS 2.3.93). It felt among the dead of China the "tiny figure of Wang Wenyi’s wife lying at [it’s] edge…, the blood from her wounds staining the water around her" (RS 2.3.94). Mo Yan even brings the river’s collaboration one step further by having the "tiny ripples on its surface" "pulverize" the "heavy, dull rays of sunlight" that dared to shine light on the massacre of so many people (RS 2.3.93).

In Red Sorghum, Mo Yan makes a statement about war and its effect on people and nature. He shows the connection and dependence between man and nature, in this case, the Black Water River. The river expresses the emotions for a people unable to. As a central part in their lives, the river participated and collaborated in the violent acts the Chinese committed in revenge and anger, but also served as their emotional release.

© Meagan Gates, 2001

References are to Mo

Yan. Red Sorghum: A Family Saga.

Trans. Howard Goldblatt.

1993

Viking Penguin. New York:

Penguin-Viking, 1994.

Dialogue #3

Humanities 210 (Spring 1998)

CHINESE TRANSLATION ISSUES

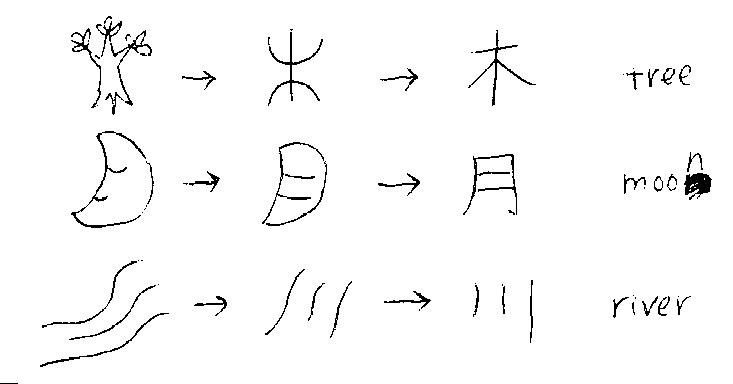

It is said that Kanji was brought to Japan from China around the first century AD [or CE]. However, Japanese use only a few thousands of Chinese characters which are not that old....So if it's written in easy kind of Chinese character, we can "guess" what it's said, as when I was looking for a bathroom in China: I saw three Chinese characters which mean "water," "wash," and "place"; then I assumed it must be the restroom. Chinese characters are pictographs symbolizing physical objects; each character has meaning:

|

../asianimages/kanai1.jpg

Two or more elements, each having its own meaning, form a character:

|

bright (sun + moon) |

| relax (person + tree) |

../asianimages/kanai2.jpg

Therefore, the advantage of Chinese characters is that you can often associate the meaning of the character with the shape of it, even if you don't know the pronunciation.

In a poem "Secret Courtship," I don't see any big differences between two translations [given in class handouts]. The word "leap into" might be a little awkward for English speakers. But I think the original Chinese character for "to leap into" is also translated as "to climb over" depending on the situation, since one Chinese character has usually more than two meanings, or at least two ways to translate. The word "care" seems to me the same as "mind." The word "words" is exactly "what they say." If I were a native English speaker, I might feel it a little strange if it didn't sound right to me, but I think a bit of awkwardness makes foreign poems even more exotic and we would enjoy it. So I would prefer reading foreign poems with the translation by a native speaker of that language first, and enjoy their word choice or way of expression. Then I'd read the one by an English speaker later if I didn't quite understand the first one. Actually, examining the differences is interesting too.

© Mayumi Kanai, 1998

Izumi

Ota

Dialogue #3

Humanities 210 (Spring 1998)

CHINESE TRANSLATION ISSUES

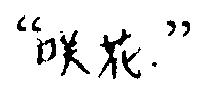

I chose [topic] #1, translation issues for my Dialogue #3. From my translation experience, I can tell you some things. I do not really know Chinese character very well, but because Chinese and Japanese characters are similar, I can tell you some of the difficulty when we translate from English into Chinese. I picked up three main things that might help you to understand.

First, English...alphabet...has only 26 characters, but Chinese...has more than thousand of characters. Chinese is more like Japanese. In English, each [letter of the] alphabet does not have a specific meaning, but in Chinese each character has [a] different meaning and we can make [an] easy sentence with two or three characters. For example:

| For example: |  |

../asianimages/Ota1.jpg

|

is one character, and |

|

is one character. |

../asianimages/Ota2b.jpg

../asianimages/Ota3b.jpg

When I put these two together, it means, "The flower is blooming." [But i]n English, I [must] use 19 letters to explain these two Chinese characters.

Second, it is very difficult to find exactly the same word in English and Chinese. English words have many meanings in one word, but Chinese character has only one meaning in each....For example:

| This word, in Chinese, has only one meaning. |

But in English, there are many words which explain this word: thick, strong, deep, dark - these are all [English] meanings of:

| the Chinese symbol: |

Third, depending on the person who translates, the translation is different. If a Chinese person translates, the poem will be translated more like Chinese style and more understandable for Chinese people, and if an American person translates, the poem will be translated more like American style and more understandable for American people, because each person has different cultural background and thought about translation. These create different translations of articles and difficulties of translation.

I read the Chinese poem which is [called] "Secret Courtship." I like Translation #1 [handout] because the translation is not too specific and more like a poem. Translation #2 [handout] is too specific and more like an essay. For example in [Translation] #1 poem, the author uses "parents" instead of "father and mother." It is more comfortable for the reader. Using "father and mother" makes the poem more like an essay and I do not feel familiar with it. And, I also like the way of Translation #1--the sounds--so I prefer Translation #1 of the poem.

© Izumi Ota, 1998

Marie Kay

Patteeuw

Dialogue # 3 - Part 2

[Hum 210, Spring 1998]

CONFUCIUS AND WOMEN

Confucius was said to be a noble, honorable teacher. He was also known to be affectionate and sympathetic toward others (packet 144). That is unless you happen to be a woman. Confucius believed that women were of a lower status than men were. He was also quoted in saying "One of a women’s virtues lies in her ignorance"(153). Considering the amount of followers in China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam, his teachings had an incredible impact on the lives of women. As you can see the impact was not a positive one. Although, according to Shu if you think something is going to be harmful to yourself than it would probably be harmful to others. Confucius defined Shu as "Do not impose on others what you do not wish imposed on yourself" (148). So why does the Confucian beliefs impose such shame on women?

A Chinese poet, Fu Xuan* wrote a poem that showed how difficult it was to be a woman in China. This is what she said: "How sad it is to be a women!! Nothing on earth is held so cheap." Her words are bursting with sorrow and shame. Women were even told how to act around their husbands, friends and children (153).

More recently boys are still considered la more

valuable asset than little girls. Girls are aborted or given to

orphanages. As Fu Xuan put it "No one is glad when a girl is

born." My conclusion from the reading and poetry is that the

status of Chinese women is very low. Women in China are not

considered to be valuable assets like their male counterparts.

They seem to forget that if there were no women there would be no

men.

[*Fu Xuan's poem may be found in chinalinks]

© Mary Kay Patteeuw, 1998

Mary Uhland

Dialogue #3 - Part II

Engl390 (April 27, 1998)

[Film vs. Novel]

Learning about other cultures is not confined to intellectual understanding. One also learns through emotion and sensation. Just as a human being is more than just her mind, a culture is more than just its ideology. Translation, whether through written or cinematic forms, does not provide the truest understanding. Ideally, one should learn about another culture in its own language. The written and spoken words, inflections and rhythms all contribute to the sensation and emotion elicited, quite often sub-consciously, by the poems and stories. Since it is not often possible to read them in their native language, one is forced to use other culturally colored imaginations to fill in the gaps.

I enjoy learning about a culture through reading its literature and watching films for different reasons. When I read the poetry and the novel, I am able to form my own interpretation of ideas and emotions. I am hoping that the overviews of India and China along with our class discussions help to inform this interpretation. The conflict in the stories and poems point to the values and perceptions of a culture regarding human events. If we trust the translation, the word choices will color visceral sensations. The leisure with which I can read the written literature provides more of an opportunity to look at the culture from different angles. This may allow me to get a closer understanding of the particular culture. I can ask questions, compare and contrast cultures and generally take the time to deal with a cultural statement more holistically. It is the details of the written word that provide richer insight. For example, in reading Dream of the Red Chamber, I came to understand just how important familial relationships and protocol are to the Chinese. One can hear a general statement that these relationships are extremely important to the Chinese, but to a resident of the U.S. this could mean something completely different. Our definition of family is so opposite from the Chinese. This makes it very difficult to conceive of the complexity of delineation. It is through the many different titles and manners of address one begins to understand. The complexity demands that time be taken to work out relationships. The "weight" of it all is nicely conveyed through the written word.

Film, on the other hand, provides a drastically different exploration of culture. One has less participation in the formation of ideas about a culture. The speed with which the story is told does not allow the viewer to dwell on a particular point before moving on to the next one. The nature of film dictates that much of the experience will be subconscious and this also limits the viewer’s capacity to ask questions and make choices about the information being presented. One must rely on the interpreter, but much more heavily. The story isn’t told through dialogue alone. Cinematic techniques such as visual sequence are much more fluid. Lighting and visual design influence mood. The actors’ interpretations of character influence their motivation. If they are all products of a different culture, as they were in Mahabharata, this can have a profound affect on the story. All these variables can limit the viewer’s understanding of a particular culture. After watching Mahabharata I felt that I understood the production’s interpretation of Indian ideals from one vantage point alone. I felt there was a greater distance between myself and the Indian culture.

One must consider the nature of the literature being interpreted. Dream of the Red Chamber conveys a story through particulars and lends itself well to personal identification with the characters. Mahabharata is an epic poem whose characters portray large, universal ideals. It is much more difficult to personally identify with the characters. And yet, through the process of dramatizing the epic poem, the viewer may be able to identify with the characters more so than reading it.

It seems to me that the best approach to exploring another culture would be through many avenues - reading, watching, conversing and experiencing. All of these are tools offering different perspectives that enhance the synthesis of the intellectual, emotional and sensational elements of a culture.

© Mary Uhland, 1998

Unsigned ![]()

[by Hum 210 student request]

Dialogue #2 - Mahabharata

(Spring 1998)

THE GAMBLING MATCH

The gambling match in Mahabharata was deceptive and was originally intended to destroy a person. Really the gambling match in Mahabharata is no different than a typical poker game here in the U.S..

Yudhishthira was lured into the gambling match. Duryodhara and his uncle Shakuni knew that Yudhishthira could not say no to a gambling match because they new that he had a gambling addiction. Also, I believe that it would have been dishonorable for Yudhishthira to refuse the gambling match. He would have "lost face" so to speak.

The scenario is typically the same here in the U.S. when it comes to a poker game. People who gamble on a regular basis would not be able to say no to a poker game. Maybe because they are addicted to gambling or maybe because they would "loose face" if they turned down a poker game. At any rate, the idea is the same for the gambling match in Mahabharata and for people today. It seems that men somehow preserve their manhood by not saying no.

In the gambling match in Mahabharata, Duryodhara and his uncle Shakuni lured Yudhishthira into the game knowing that he could not say no to the game. Duryodhara and his uncle also knew that Yudhishthira had many valuable possessions to loose. Shakuni kept winning and the stakes kept getting bigger until Yudhishthira had lost everything. Again, Yudhishthira could not quit the game even though he was losing everything, probably because he would be marked as a coward or a quitter or something like that. His manhood would be at stake in other words.

Here, a poker game is very similar to the gambling match in Mahabharata. Once a gambler is in a game, they usually play until they have either won everything or lost all the money that they had brought with them. Of course, the scenario is the same as in Mahabharata in the since that a gambler could not quit in the middle of a game for fear of being marked as a quitter or something to that effect.

Maybe there is a moral to the story of the gambling match in Mahabharata. Maybe the story is trying to say that perhaps gambling is some sort of sin against the gods. And that one who partakes in such things will suffer some sort of fate. The fate being, in this particular case, loosing everything.

It seems that the same thing is true here in the U.S. Gambling is deemed to be some sort of sin by many different religions. And it is known to be true that people suffering from a gambling addiction have been known to loose every thing that they own.

I find it interesting that a piece of

literature written about an event that occurred between 1400 and

800 B.C.E. could have many similarities to events that occur

today.

Reference: (Hum 210 packet pp.73)

© Held by student: Published Anonymously with Student Permission, 1998

Meagan

Gates 1

HUM 210

Dialogue #3

26 Feb. 2001

sound

of solitude

where snow falls on the pine trees;

death stalks the foolish.

A

week ago or more, I was standing alone on our front porch, enjoying watching the

snowfall. I think I stood there for fifteen or twenty minutes just appreciating

the beauty of it and realizing how we really need it for the summer. Then I

began to get really cold. I realized I wasn’t wearing a coat, and how stupid

that was. I was a long way from hypothermia or frostbite but I sure was feeling

the cold. While snow is a very beautiful and peaceful thing, it also struck me

how lethal it is for those not prepared for its other qualities. More than

hypothermia stalks the unwary in a snowstorm – bobcats and other predators

also hunt.

For

the haiku itself, I used the concrete image snow falling on pine trees to

suggest the winter season. My cutting word was ironically "death." I

was at a loss at first as to what I was going to write about, but then I

remembered how I felt in the quiet "solitude" of the falling snow. And

there was my "haiku moment."

©

Meagan Gates, 2001

Cathy

Hosford

Dialogue #4

Engl 390 (Spring 1998)

Haiku for You

My daughter

and I

Passing thoughts and a football

Springing together.

This haiku is for when my daughter and I were passing a small football back and forth in the living room in the late afternoon and just talking about all kinds of stuff.

Glowing

purple haze

We stop and gaze and say "WOW"!

Spring painting by God.

This haiku is for when the sun was setting and my daughter and I looked outside and were enjoying it. I took some pictures of it with the lilac trees in the foreground. It was a very beautiful sight.

Written by

Cathy Hosford

May 3, 1998

© Cathy Hosford, 1998

Mayumi Kanai

Dialogue #4

Hum 210 (Spring 1998)

|

.../hum210/asianimages/haiku.jpg

Haiku

Sunflower

peeping at the glaring sun

over the fence.

Summer has come, but sunflowers are not quite grown yet--not as tall as fences. They are in a hurry to become taller so they can enjoy 100% of the sun of summer.

Seasonal word is "sunflower" = summer. But this should be early summer because of the restlessness of the flowers.

I'm not sure how we do 5-7-5 in English. This method seems to be impossible in English. Besides, haiku is very short and grammar is often fragmentary.

The Japanese order of thought often is the exact opposite of English. In English [i.e. in Japanese] I would put the word "sunflower" in the last. I think Japanese tend to say what they want to say most in the last. They often take up the main issue after a few introductory issues. That might result in not telling their honest feelings first, and later it gets harder to say "no." I've heard that Japanese people don't say "No" clearly. I must admit it....

© Mayumi Kanai, 1998

![]() Nobuhisa Kondo

Nobuhisa Kondo

Dialogue #4

Hum 210 (Spring 1998)

Haiku

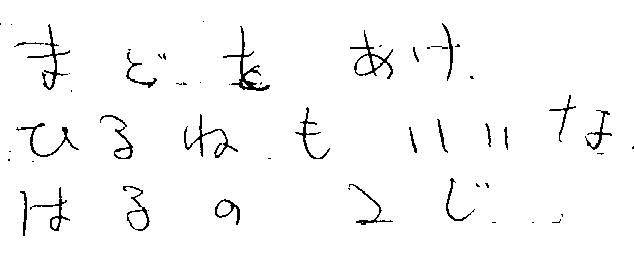

In Japanese:

|

5 |

| 7 | |

| 5 |

../asianimages/Kondo1.jpg

--to pronounce:

| Ma do wo A ke | |

| Hirune mo i-i -na | |

| Haru no ni-j-i |

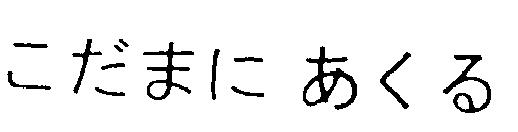

--translated into English:

| Open the window | |

| Taking a nap is good, too. | |

| A spring day, 2:00 p.m. |

I wrote this haiku in Japanese first, and translated into [English]..., so it might not make sense in English if my translation was not very good. Anyway, I like to take nap, and a spring day is a better time to take a nap. That's why I made this haiku. Open your bedroom window and take a nap at 2 p.m. on a spring day. I mean, there are lots of other things to do on a spring day, like playing soccer or going to swim....but taking a nap is good. That's why I put "too" in the second line of this haiku. I tried to use "kigo," a seasonal word, and "spring" is that, as you know.

© Nobuhisa Kondo, 1998

Shannon

McKenzie

Dialogue #4

Engl 390 (Spring 1998)

Haiku

In the dawn of morn

a weak new-sprung blossom

sheds its life

The haiku I created represents the beginning of spring and the brand new flowers that are beginning to bloom. I produced this haiku because I love Spring and I’ve recently noticed the new flowers around my house that are coming up. There was one flower in particular that this poem is about. Every morning I have to leave my house at 6:25 am in order to be at work on time. Fortunately, the sun is just beginning to rise at this time and I get to watch the beautiful sunset. One morning, I was walking to my car when I noticed a small flower just beginning to bloom near the edge of my driveway. I remember thinking that this was odd because I hadn’t planted any flowers that close to the pavement. I also noticed that this flower was all by itself and it looked exquisite because it was alone and it was blooming in the early morning sunset. The flower, the sunset, and the beginning of Spring is what I decided to interpret in the form of a haiku because of this experience.

The examples I was trying to follow when writing my haiku resemble the examples of the haiku’s in the Hum. 210 course pack on page 233. I really liked the Haiku #4 because it is clear and portrays a specific image. I tried to create a haiku that created an image similar to the Haiku #4. I wanted to be as simple as possible, but at the same time provide a clear image. I hope my haiku will be interpreted this way. It took me a really long time to come up with this haiku. It looks like it is really easy to create a 3 lined poem, but I learned that choosing the right words was extremely difficult . I really enjoyed this dialogue and I’m actually excited that I wrote my first Haiku!

© Shannon McKenzie, 1998

Izumi

Ota2

Dialogue #4

Hum 210 (Spring 1998)

Haiku

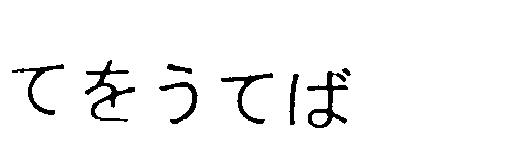

I created this haiku:

|

|

../asianimages/Izu1.jpg

../asianimages/Izu2.jpg

When I walk up to the hill, I can see the spring haze. I usually come to COCC by driving, but one morning, I had a chance to come to COCC by walking from my friend's house, because I spent a night in her house and I had no car. It is very hard and made me tired to go up to the hill, which I have to pass to go to COCC. It takes 10-15 minutes to get to my classroom. While I was walking, as it was very early morning and it was very cold, I could see the haze. The haze was very beautiful for me. Also, I smelled spring when I saw the haze. It was cold but I felt that spring is carried by spring wind with beautiful haze. Usually, I don't like the haze because I can't see clearly when I drive. I usually come to school and [so] I missed a lot of beautiful things. I found beautiful spring by walking up to the COCC hill.

Making haiku is not very hard for me. I have learned making and learning haiku for 4 years when I was in Japan. I guess making haiku in English is hard because English is pretty different than Japanese haiku. English haiku does not make any sense for me....In my haiku, "kigo" is "haru Gasumi," which is "spring haze." When you hear my haiku in English, you might think it's quite simple and sounds not very interesting but when Japanese people hear it, they think it sounds interesting. I wish you were Japanese and you could have a nice moment with my Haiku...that's too bad....Japanese and American have quite different taste of haiku....so....

© Izumi Ota, 1998

Keiji

Oto

Dialogue #4

Hum 210 (Spring 1998)

Haiku

A spring breeze

take me to the

full of dream

I got a rise to this haiku when I came to college by bike in one warm morning. There are several cherry blossoms on my way to college, and I was fascinated by the fall of petals. That view was a little sad, but on the other hand, made me think where those petals could go.

No reason

having hair cut

a spring wind

Being released

quick caught by

a floral melody

A pancake

too much water

thin like me

--by Keiji Oto

© Keiji Oto, 1998

Unsigned

[by Engl 390 student request]

Dialogue #4

(Spring 1998)

Haiku

Cleaning

chicken house

shoveling droppings within

spring baby chickens

This weekend I had the opportunity to clean my chicken house. I have long awaited the opportunity to get this task completed. I like the task only because I know that the rewards are great. I think about the chickens and the amazement of how they actually produce the egg. I like to collect the eggs each day—it’s like an Easter egg hunt every day. I was also preparing for the long awaited arrival of new baby chicks. Every year I anticipate the purchase of new baby chicks to fill my chicken yard.

I have learned that composing haiku gives you the opportunity to feel the moment again as you write about the experience. It allows you to go deeper into the treasured moment. I used several of the different examples of haiku to help me create my own haiku. I tried to look at the "housecleaning" haiku. I included a kigo (seasonal word) and the specific amount of syllables (5-7-5) that are required for a haiku. I thought the process of writing this haiku was fun and challenging.

© Held by student: Published Anonymously with Student Permission, 1998

Unsigned

[by Engl 390 student request]

Dialogue # 4

(Spring 1998)

Haiku

The wind

through the trees

The eagle soars with the air

A silent forest

My haiku moment came as I was driving home from school. I was having a bad day and the weather outside was stormy and wet. As I was driving I saw a large bird flying through the air. He seemed unaffected by the storm as he flew through the sky. From seeing this I started to think how I could make this incident into my haiku moment, and it worked! I would interpret my haiku as a desire to be like the wind through the trees, and have the power of an eagle to soar through the sky and be near the tranquility of a silent forest.

I found it challenging to write a haiku. Many of my thoughts were hard to turn into the simple 5-7-5 format. Those that did fit into the format just didn't seem powerful or the images were not contrasting enough. When creating my haiku I tried to follow the simplistic yet contrasting images of Basho.

© Held by student: Published Anonymously with Student Permission, 1998

Chad

Brown

Discussion Paper #1

Humanities 210

May 26, 1998

Drinking With Li Po

I met with Li Po at his small house in Shantung. We were planning on traveling to Szechwan, his childhood home. It had been a long time since I had last seen my old friend; I was looking forward to hearing about his life since we had last parted.

"Chad, I am so happy to see you again. Come, let us be on our way, I haven’t traveled in a long while and I am beginning to lose my mind."

We headed off down the road, stopping often to take in the beautiful scenery of China. It wasn’t too long before night fell upon us. We decided to stop and rest for the evening. We had been walking for a long time, and we were quite thirsty. Luckily for us, I had come prepared with many bottles of wine. With the wine coursing through my veins, I asked Li Po about his poem, "Drinking Alone Under the Moon."

"Li Po, would you rather drink and write poetry by yourself, or with friends?’

"That is a very hard question to answer," Li Po replied. "Drinking alone puts me into an introspective mood. When I am by myself, I find that the poetry I write has more personal value. It may not be what others want to hear, but to me it is the embodiment of my very soul.

When I drink with my friends, I find that my poetry becomes lighthearted. It is hard to be in a bad mod when one is drinking amongst friends. I think that the majority of people who read my poetry prefer these kinds of poems."

"But Li Po, I think that your poems about drinking alone are models of near perfection," I stated.

"Well Chad, you are one of the few exceptions. I myself prefer the poems of mine that are written in solitude, but sometimes there is no greater joy than drinking and writing with friends. Plus, you don’t have to worry about finding your way home when you drink with friends."

We rose early the next morning and continued on our way to Szechwan. We remained silent for much of the afternoon. The day was so beautiful that neither one of us wanted to spoil it by breaking the silence. I began to wonder why Li Po wanted to go back to Szechwan. I recalled his poem "The Road to Shu is Hard," in particular the line, "I sigh and ask why should anyone come here from far away?" It wasn’t my idea to travel to Szechwan, in fact, I wanted to visit the Han-Lin Academy, where Li Po used to teach; but he was very adamant about going to Szechwan. I finally decided to break the silence.

"Li Po, why are we going to Szechwan? You yourself said that the road to Shu is hard. If it’s so hard, then why are we going?"

"Chad, I am no longer a young man who can travel anywhere he pleases. I have lived a long and fruitful life, but I am afraid that my days will soon be up. Indeed, the road to Shu is hard, but it is a journey that I must take one last time before I die. Now give me a bottle of wine, this morbid conversation about my death has put me in a somber mood. We need to get some drink in us before we start crying like schoolgirls."

Li Po and I drank for most of the night, singing songs and spouting drunken poetry. We successfully avoided bringing up the subject of death.

I woke up the next morning to see Li Po draining the last of the wine.

"It seems as if we have run out of wine," he said. "First chance we get we’ll stock up on some more. Let’s be on our way, I want to reach Szechwan before tomorrow night."

By midday we reached a small tavern. We bought six more bottles of wine, ate some lunch, and then continued on our way. It was an uneventful day, Li Po didin’t talk much; when he did open his mouth, it was only so he could take a drink of wine. When we stopped to camp for the night, Li Po immediately went to sleep. He wanted to be well rested for tomorrow’s journey. I used the time alone to work on my own poetry. Although it wasn’t exactly a masterpiece, my poem was still very important to me. It was a testimony of my friendship with Li Po. I decided that I would give the poem to him when we reached Szechwan.

We woke up early the next morning, and began the last leg of our trip to Szechwan. As we got nearer and nearer to Li Po’s homeland, I began to wonder why he thought the road to Szechwan is hard. It certainly wasn’t a difficult journey. Even the most inexperienced hiker could make the trek without breaking a sweat. But as I looked around me I began to understand. The scenery was so beautiful that I felt as if I could sit down and stare at it forever. I stopped for a moment to gaze at Six-Dragon Peak, wondering what it would feel like to climb it’s summit. I looked below at the winding river, wanting so much to be a part of it. I realized that this is why the road to Shu is so hard. Observing, even for a moment, the sights and sounds around me, made me want to stay there forever. Li Po snapped me out of my trance.

"I used to travel all over China, searching for the Tao, the unnamable way of truth. I always felt that if I journeyed far enough then I would find it. But it always seemed to slip my grasp. I was always right behind it, chasing after it until I became exhausted. No matter how hard I tried; it was always one step ahead of me. I believed that the Tao was universal, that it was the same for everyone; but I now know that I was wrong. The way of truth is different for every human being. I feel that by journeying back to the place of my youth, while I myself am getting ready to die. I think that I have finally found the Tao."

"How do you feel?" I asked.

"I feel like having a drink," he replied.

Li Po and I both knew that we would be going our separate ways once we reached Szechwan, so we didn’t waste time with a drawn out farewell. Li Po and I shared a final glass of wine, gave each other a hearty hug, and said goodbye. Li Po traveled towards a welcome death, I towards an unforeseeable future. As I began my long walk home, I smiled to myself, hoping that Li Po would enjoy the poem of mine. The poem I gave to him before we parted ways.

Good

Company

Drunken old man, wise

old sage.

Together we sit in the grass, bottles in hand.

We have traveled far together.

And gained little from our journey.

But I am drunk, and in good company.

That alone, is enough for me.

© Chad Brown, 1998

Mayumi

Kanai

Discussion Paper #1

Humanities 210

Asian Poetry in Translation

As Robert Frost said, "poetry is what gets lost in translation," especially when it's translated into English from Chinese or Japanese, which have very different sound structures, grammatical features, and systems of writing. Depending on the translation, preserving the integrity of the structure, form, rhythms, and music of a poem, or capturing the literal meaning of the words, a poem can be slightly different and you'll find what may be lost by comparing two translations.

Because of the absence of tenses, of personal pronouns and of connectives, Chinese poetry may vary interpretations. It is no wonder that critics and annotators have differed as to the meaning of poems in Chinese. Also, for readers in English, sometimes it is better to eliminate or use only seldom the names of places which are familiar in the Occident. However, the places which come up to poems have special spiritual climate which is very significant to the poems. Therefore, the translator would have to try hard to convey the significance to non-native readers, while too much explanation can take the pleasure out of poetry. Also the translator avoids phraseology which, natural and familiar in Chinese, would be exotic or quaint in English. To appreciate the masterpieces of human and universal qualities they [Chinese] endured in their lives, this might be a good idea to read poems in two or more translations with a wide range of interpretation.

As Arthur Waley remarked, "of all poetry Japanese poetry is the most untranslatable." An ideal translation is expected to reproduce the effect of the original in Japanese poetry. However, there are certain particularities about Japanese which make absolute literalness practically impossible. For example, there are no articles in the Japanese language, no pronouns, and no distinctions between singular and plural. This compactness helps Haiku rhyth[m]. In Haiku there is no punctuation, so it's often taken place [instead] by cutting the last words to indicate an unfinished sentence and to make an elusive force...which have no translatable meaning. Also the Japanese language is constructed differently from English. This could give a translator the dilemma of whether to follow the strict grammatical form or the order of thought, or sometimes to supply more important words which are implied but no expressed in the original. This [practice] can be very helpful to understand the sense clearly if the translations are not much too long.

I have found that some poems are over interpreted or lack explanation in translation. For instance, in "One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets," which were selected in the third decade of the thirteenth century, there is a poem by the Priest Ryousen.

Sabishisa ni yado wo tachidete nagamureba

izuko mo onaji aki no yuugure

The Japanese order is literally:

sad, lodge, get out, view

wherever, same, autumn, twilight

Translated in "One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets," by H. H. Honda (1956):

Sad, I wandered out, and weary,

To soothe my mind, but everywhere

Did I see the shadows dreary

of autumn twilight in the air

As far as I remember what I learned in school, this poem was written when he [Ryousen] was living with strict discipline to become a priest away from home and...he was homesick. He was sad with everything different from his hometown which he was not able to adjust himself to, but he found one same thing which reminded him of his home: the beautiful twilight. The English translation doesn't mention about the word "same."

Here is another example:

Hito wa isa kokoro mo shirazu furusato wa

hana zo mukashi no ka ni nioi keruby Kino Tsurayuki

Literally translated into Japanese:

people, what they are thinking, unknown, my home,

flowers, years ago, fragrance, smell

Into English [also H. H. Hondo??]:

How the village friend may meet me

I know not, but the old plum flowers

Still now their fragrance greet me

kindly as in the bygone hours

Kino, I don't recall why, had to leave his town for some reason. When he was coming back after years, he had kind of a guilty conscience and he was very nervous wondering what the village people would think of him. It had been years and people would have changed. However, he was glad to know that the flowers smelled the same and he felt he was heartily welcomed. I can't tell his anxiety and the probability of coolness of village people in the English translation quite well. Also I wonder why "plum" came up in the English translation. Was clarifying the kind of flowers that important in this poem?

It must be not that easy to find passable English equivalents; however, I've found a nice poem with agreeable English translation in this book (Hondo, 1956).

Sewo hayami iwa ni sekaruru takigawa no

warete mo sue ni awan tozo omouby The Retired Emperor Sutoku

Literally:

stream, rapid, rocks, rush, river water

apart, eventually, meet, I believe

In English:

As water of a stream will meet,

Though, barred by rocks, apart it fall

In rash cascades, so we too, sweet,

Shall be together after all.

Reading it in Japanese, I got an idea that even though they are apart now, they will eventually get together again as water of a stream. Though Haiku are very short, and their grammar is often fragmentary, I enjoy the word choice, order, and rhythm in this English translation. This is very pleasant to find myself becoming suddenly aware of the particular voices of a few poets among the English translation books.

© Mayumi Kanai, 1998

Nobuhisa

Kondo

Discussion Paper #1

Humanities 210

Relationship Between Zen Buddhism and Art in Japan

Lots of Asian religions are different from what Western people think [of] as a religion, belief in god. Actually, god is not so big deal in those Asian religions: those Asian religions are defined in the [Hum 210] course pack as "ways of liberation to describe these forms of spiritual experience, for all are concerned with liberating human consciousness from ideas and feelings brought about by social conditioning" (p. 219). In other words, those religions try to lead people to the beyond of the world which we perceive only through our senses. One of those Asian religions, the ways of liberation, is Buddhism.

Buddhism was created by one of those Indian countries' princes Gautama Buddha and was developed by his students in the Mahayana school, one of those Buddhist schools. Shortly, Buddha and his students tried to correct the misunderstanding of liberation; people thought that liberation was just an escape from suffering or a permanent state of bliss. Those Buddhists taught people that if we do prepare for our death, there is nothing that scares us, and we also do not have to act for hope of reward or fear of punishment...[or for] "Human conventions necessary for social existence but without any absolute authority" (219). Buddhism was introduced to Japan in 539 AD through India, China, Korea, and Japan cultural trading routes and developed into one of the two biggest religions in Japan, Buddhism and Shinto.

Zen / Ch'an Buddhism

Zen Buddhism was developed in China as a result of the conflicts between the Mahayana school and the Taoism, Chinese philosophy. Zen Buddhism was introduced from China through Japanese who studied in China in tenth and eleventh centuries. Zen and Ch'an are the Japanese and Chinese words which mean Dhyna in Sanskrit, suggesting the meaning of "a state of mind roughly equivalent to contemplation or meditation, although without the static and passive senses that these words sometimes convey" (course pack). The Dhyna is described as the state of consciousness of Buddha; in other words,...explained in the course pack as "one whose mind is free from the assumption that the distinct individuality of oneself and other things is real." This relationship among all objects in this world is called their "voidness," because "nature cannot be grasped by any system of fixed definition or classification. Reality is the 'suchness' of nature or the world 'just as it is' apart from any specific thought about it." (This is very difficult to explain in words.) Actually, all of Zen Buddhists practice to understand this Dhyna and voidness.

Two Major Practices of Zen in Japan

To get those Dhyna and voidness, or suchness, Japanese Zen Buddhists created some interesting practices which cannot be found in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism. Two of those practices are zazen and haiku. Zazen is a practice of meditation where students just sit on the floor and observe everything "just as it is," even themselves. They are expected to meditate without any mental comment on what ever may be happening, but just to observe.

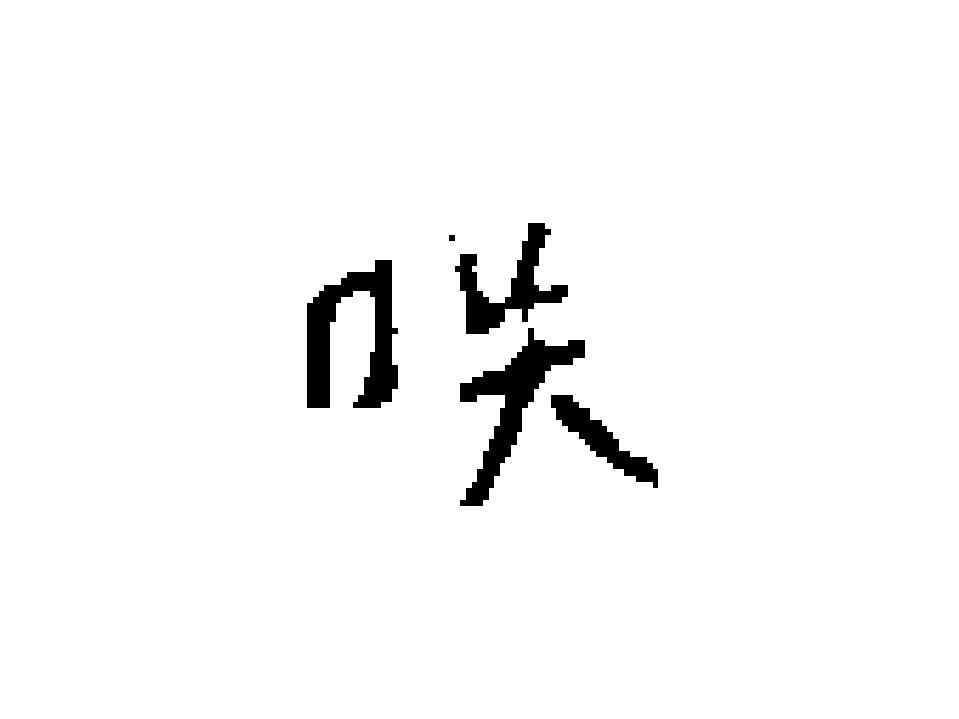

Haiku is a kind of Japanese poetry which consist of 5-7-5 syllables, a very short verse form. This Haiku was also used for Zen students to perceive the world "just as it is"; Haiku was also used as an entertainment during the Do period. This 5-7-5 haiku form was created and developed by a Do period poet, Matsuo Basho (1644-94). Basho is known as the greatest master of haiku even today. here is one of his haiku as an example.

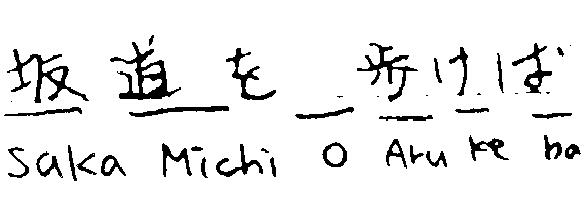

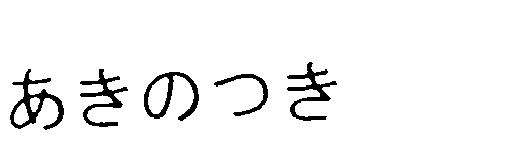

In Japanese:

|

5 |

|

7 |

|

5 |

../asianimages/Kondo2a.jpg

../asianimages/Kondo2b.jpg

../asianimages/Kondo2c.jpg

To pronounce:

Te wo uteba

Kodama ni akuru

Aki no tsu ki

Translated into English:

As I clap

my hands,

with the echoes, it begins to dawn--

the summer moon.

This is one of those haiku which Basho wrote in his most popular book, Okuno hosomichi. Just to make this poetry book, Basho traveled the northern part of Japan; at that time, not many people traveled the northern part because [they thought] there was nothing in the northern part. Most haiku are written just to describe a moment of the scene, the moment of a crow left a branch of pine tree, or the moment of dew dropped from a leaf in the summer dawn, and so on. Therefore, it is important to imagine the moment of that haiku was made when you read a haiku. Read this haiku a couple of times and just close your eyes and imagine the scene; you can even put yourself into the scene instead of Basho, like you made this poetry. It is the moment that you clapped your hands in the mountains, no one else is there but you. Japanese summer is so hot and humid even in the northern part, but this poetry was written in the dawn, so it is cooler now and you feel comfortable in the coolness of the dawn. You still can see the moon on the dawn sky, and the sound of your clapping hands echoes over the mountains and comes back to you. This is the situation and moment that this haiku was made. Don't you feel comfortable and feel good now? If you do, you got some part of the "voidness" and "suchness" of Zen Buddhism through this haiku practice.

© Nobuhisa Kondo, 1998

Mo Yan Paints Red Sorghum

Skimming through the first twenty pages of Red Sorghum, the words blurred together like the gray chalk of dirty newsprint. After the in class dialogue about topics, themes, style and character, I began to read Red Sorghum with new eyes. Words do not penetrate my consciousness the way that direct experience and sensory understanding do. Covered with ripped and scribbled post-its, my copy of Red Sorghum now looks like an artistic collage of paper on paper. Each shred underlines or redirects my attention to the use of color in the descriptive writings of Mo Yan. My understanding of color theory and my own love of color and its relationship to the visual world made this novel come alive. The colorful descriptions of the people, events and backdrops in the book represent one of the many keys which Mo Yan offers as entry into the world he creates. I have used the visual language of Red Sorghum to penetrate and understand the story as it unfolds.

Scarlet, the deep red of a boiled chicken liver, beet-red, a sapphire sky, red butterfly, red warmth, as red as rubies, red paint, red morning sun, glossy red, and bright-red blood are a few of the shades of red that Mo Yan uses to wash the pages of Red Sorghum with the colors of life and death. Used to describe everything from the color of wine to the passionate blur of a sexual encounter, Mo Yan not only describes events with the richness of color but also creates a tinted screen, which we are able to hide behind as we witness the violence or intimacy of the events that he describes. We begin to notice as the plot thickens, a buildup toward a major event in the book. Mo Yan turns up the intensity, using color; he directs the surroundings to become more vibrant. During the main episodes in the book, we see the concentration of the use of color as a metaphor for action, murder, life, and nature. When Second Grandma is brutally raped and murdered along with Little Auntie, the description of the bedroom door is predominantly through the use of color. (p. 324) Also the brutal death scene a page later, shows Second Grandma’s death as a quick journey into a yellow haze, followed by a green light, finally being “swallowed by an inky black tide.” (p. 325) During many of the everyday descriptions or events, the canvas stands less defined. Mo Yan’s palate serves as a tool for intensifying the mood, events, and surroundings of his writing. It becomes a visual device beyond words to add description and mood to the story.

Earlier in the term we had discussed issues of translations. As I read through the book, I began to wonder if the color red had been approached generically in translation. I noticed that the same description of a particular color was used over and over again. For example “a trickle of bright-red blood” (p. 286, para. 4), “a blood-red bolt of lightening” (p. 46, para. 5) and “streaks of blood-red lightening crackled” (p. 50, para. 3) are very similar in their descriptions. Also, the word scarlet is used continuously. Red could have hundreds of descriptives such as crimson, scarlet, auburn, ruby, burgundy, cherry, and even more nouns which descibe the color like wine, apple, flowers, lacquer, etc. Many times we do see the use of color related to specific objects and Mo Yan does use elements

of nature to describe places. Scarlet seems to occur generically as a constant tone of red. The use of blood red does support the theme of war and violence. I began to wonder if like the Inuit, with their hundreds of words to describe snow, perhaps the Chinese with their appreciation for the visual world and ornament had a few more shades of red to offer in this text.

Color theory comes into play as Mo Yan begins to combine the colors of his novel. Artist learn that using colors that are in opposite positions on the color wheel, when placed side by side, assist one another in becoming more vibrant. Conversely, when mixed together these complementary colors combine to make an uninspiring gray. In the same way that red is used to describe the vibrancy of life and death, green is used to describe anger, envy and decay. During Uncle Arhat’s execution, we see his eye described as “slits through which thin greenish rays emerged.” (p. 34) His fear and hate are described perfectly through a simple discription of this magical glow. In describing the devastation of the Japanese invasion we see the Black Water River, full of animal and human carcasses described as “…their splendid innards, like gorgeous blooming flowers, as slowly spreading pools of dark-green liquid were caught up in the flow of water.” (p. 39) The simultaneous use of green a red to describe the sorghum is a method for contrasting the good and the bad. Much as Grandma’s death is described as it moves from shades of red to green, “Her blood stains his hand red, then green, her unsullied breast is stained green by her own blood, then red,” (p. 37) we see the color intertwined just as life and death mingle in this mortal world. Mo Yan is combining these colors to exemplify and intensify the elements of the scene. On the verge of mental collapse, Grandpa sees “streaks of red and green flashing before his eyes.” (p. 173)

Green is also used to describe a variety of omens. The “gray-green sow bugs,” (p. 32) “green-tipped sorghum,” (p. 59) “he saw a flash of green,” (p. 160) “green-backed grass carp,” (p. 179) or “a dozen pair of green eyes” (p. 179) are all examples of symbolic animals or colors which mark a change or the coming of death or violence. The green-eyed dogs are described again on page 180. Multiple references to the “Japanese dogs,” enable us to see exactly what the Chinese thought of the opposing troops. By describing the dog pack, we are witness to the true nature of living animals. Man’s best friend ultimately turns on him, often violently. The relationship between Father and his child army becomes a living breathing parody of the war. Through the dogs, we see that war ultimately brings out the beast in the soldier. The visual description of the relationship between Father and the lead dog gives us full understanding, “Red glared at him hatefully.” (p. 212) Mo Yan limits his palette to red, green, and black. The three lead dogs in fact are called “Blackie, Red and Green.” (p. 203) Black is often used to describe unmovable and ultimately bad elements. The black Japanese uniform, black cars, and the ominous black locomotive are examples. The variety of color is limited so that a dialogue between the three main colors can be simply established. Other tones and shades exist only as decoration. Violet and apricot are used sparingly. We may see the description of a sunset with soft hues. In this book there are brief reprises for moments to appreciate the few things that remain beautiful and good. The use of color was the key for my understanding of the book. By focusing on just one aspect, the shifting time frames and historical context fell by the wayside. I became guided by the color of the red sorghum.

Keiji

Oto

Discussion Paper #1

Humanities 210

Asian Poetry in Translation

[According to one source,] the Asian poetry may differ from the Western poetry in at least three ways: (1) in the use of forms employed in the West, and in the presence or absence of approximation of Western forms, such as the long narrative poem and dramatic poetry; (2) in its preference for certain kinds of metaphors and symbols; and (3) in its use or nonuse of prosodic devices that the particular language favors or discourages because of its structure, including rhyme.

A good translation needs some preconditions why translators elect to translate a poem, reasons that have to do with respect and value, and they also must have a deep sense of recognition and self-knowledge confirmed by the poems. It is essential for [translators] to read, interpret, and feel the poems, and if they really achieve these sequences, you can become creatively involved in the poem in your own way.

Personally, I understand the fundamental Chinese character, so let me translate Li Po's "Drinking Alone under the Moon," and then i think you will not have any difficulties noticing that I am a good example of a bad translator.

Between the

flowers, there is a sake.

I drink it; there is no friend or parent.

I raise a cup, and invite cheerful moon.

My shadow makes three people.

The problem with this translation may be the unclearness. I didn't interpret or feel the original poem fully, so you didn't probably find the strong loneliness which hidden under the surface.

Haiku is a poetic form unique to Japan, and is the shortest poetic form in the world. It is said that the haiku form was created in the 17th century and flourished in the Edo period when master poet such as Basho emerged on the scene. Haiku are composed of words accommodating a three-line, 5-7-5 Japanese syllabic structure. For example:

Furuikeya

kaxazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

Here is a translation of this haiku:

An old pond

A frog jumps in

sound of the water.

A basic rule holds that haiku must contain a kigo, or a word that expresses the season. In the above haiku, the frog is the seasonal word.

Waka is another poetic form perfected in the beginning of the 7th century. Its original form can be seen in the Manyoshu, an anthology of poems compiled in the 8th century. Words which express the poet's feeling or the seasonal conditions are set into a 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic structure. Without seasonal words as required in haiku, waka allows more freedom of subject matter.

Tokai

no

kojima no iso no

shirasuna ni

ware nakinurete

kani to tawamuru.

Here is a translation of this waka:

On the

white sand of a rocky beach

on a small island

off the Tokai coast

Soaked in tears

I play with a crab.

This is a famous poem by Takuboku Ishikawa. if you read it aloud, you will hear the 5-7-5-7-7 rhythm. The pleasing resonance of its words is one of the reasons why the Japanese have long cherished the waka.

Thus, the poem's content is comprehensible. There is no single word which, taken by itself, would be unfamiliar or unclear, but I don't think the poet offer those comprehensions to us. This may make you confused; in my opinion, poetry is neither expression nor creation of people, for poetry speaks its own voice. So, what could you listen to? Did my translation speak anything to you?

© Keiji Oto, 1998

![]()

URL of this webpage: http://web.cocc.edu/cagatucci/classes/hum210/students/studwrtg.htm

Online HUM 210 Course

Resources:

HUM 210

![]() Syllabus

Syllabus

![]() Course

Plan

Course

Plan ![]() Assignments

Assignments

![]() Student

Writing

Student

Writing ![]() Student

Writing 2

Student

Writing 2

![]() Asian

Film

Asian

Film

![]() Asian

Links:

Asian

Links:

![]() India

India

![]() China

China

![]() Japan

Japan

![]() Asian

Timelines:

Asian

Timelines: ![]() India

India

![]() China

China

![]() Japan

Japan

![]()